|

|

| |

|

March 2024

|

Property Sales: “Conditional Acceptance” of an Offer is Not Acceptance, It’s Rejection

|

|

“The conditional acceptance of an offer amounts to rejection of same and not the conclusion of a contract, but may be a counter–offer.” (Extract from judgment below)

A good offer comes in for your property, so you accept it. But you’re not happy with a few of the terms, so before you sign you make a few changes to the offer. Maybe they are big changes, maybe they seem inconsequential.

Either way, you are now effectively negotiating, not accepting the offer. You have in fact just rejected it. Unless the buyer now accepts your amendments in writing (by initialing or counter-signing against your alterations), you almost certainly have no valid sale.

Thinking that you have a valid sale when you don’t is a common and easily-made mistake, and a recent High Court decision shows just how important it is for both seller and buyer to be aware of this danger.

The property auction, the counter-offer, and the commission claim

- A property on auction attracted a top bid of R1.85m and after some haggling the buyer put in a second offer of R1.9m.

- The seller accepted this second offer, but critically with amendments. The parties could not agree on these outstanding issues, with the result that the seller sold the property to another buyer without the auctioneers’ involvement.

- At which stage the auctioneers sued the seller for commission, arguing that a sale had been concluded at R1.9m because the amendments to that offer were “not material” ones (in other words, they weren’t important, significant or essential terms). The terms in question related to who was to receive the agreed occupational interest and to the issue of a gas compliance certificate. Neither amendment, argued the auctioneers, was material to the sale.

- The Court however disagreed, commenting that “In principle, anything more or less than an unqualified acceptance of the entire offer amounts to a counter-offer and constitutes a rejection of the original offer.” It accordingly dismissed the auctioneer’s claim for commission on the basis that the seller’s amendments were material and amounted to a counter-offer which the buyer had never accepted. In other words, no sale agreement had ever come into existence.

So, do you have a binding sale agreement?

If the amendments to the offer have been accepted and signed by both buyer and seller, no problem – the counter-offer has been accepted and you have a binding sale agreement.

Otherwise, as our courts have put it: “When parties conclude an agreement while there are outstanding issues requiring further negotiation, two possibilities would follow: no contract formed because the acceptance was conditional upon consensus, or a contract formed with an understanding that the outstanding issues would be negotiated at a later stage.” Deciding which is which means trying to deduce the parties’ intentions from their conduct and other circumstances – a grey and specialist area requiring specific legal advice.

Bottom line

Making a counter-offer can be an excellent tactic for negotiating towards agreement, but be very careful with the concept of “conditional acceptance”. It is actually not an acceptance at all but a rejection of the offer and could well be a counter-offer requiring acceptance by the other party in order for there to be a valid sale. Avoid all doubt by making sure everything is signed and counter-signed.

As always, ask us before you sign anything!

|

|

When is Resignation a Constructive Dismissal?

|

|

“…the prospect of continued employment must be shown to have been objectively intolerable and the employee must have resigned due to the intolerable situation and not for another reason.” (Extract from judgment below)

Perhaps you are an employer, and that troublesome employee who you’ve been hoping would resign does exactly that. Saving you, as you see it, from the risk, hassle, and expense of disciplinary or retrenchment proceedings. But are you really home and dry?

Or perhaps you are an employee, driven to resign by your employer’s constant maneuvering to make your continued employment unbearable. Do you have any recourse?

The answer to both questions lies in the Labour Relations Act’s definition of “dismissal”, which includes an employee resignation when “an employee terminated employment with or without notice because the employer made continued employment intolerable for the employee.”

And when there’s a dismissal, it has to be a fair one or the employer is in for a very expensive lesson. As we shall see …

The three requirements for “constructive dismissal”?

As confirmed in the Labour Court judgment we discuss below, there are three requirements for constructive dismissal to be established, all three of which must be proved by the employee –

- The employee must have terminated the contract of employment, and

- The reason for termination of the contract must be that continued employment has become intolerable for the employee, and

- It must have been the employee's employer who had made continued employment intolerable.

Note that there is no constructive dismissal if an employee resigns for any other reason, for example “because he cannot stand working in a particular workplace or for a certain company and that is not due to any conduct on the part of the employer.”

And a test for “intolerability”

“Intolerability”, said the Court, “is a high threshold, far more than just a difficult, unpleasant or stressful working environment or employment conditions, or for that matter an obnoxious, rude and uncompromising superior who may treat employees badly. Put otherwise, intolerability entails an unendurable or agonising circumstance marked by the conduct of the employer that must have brought the employee’s tolerance to a breaking point.”

The case of the specialist fraud and risk investigator in a bullet proof vest

- A specialist fraud and risk investigator resigned from his employment with a bank after 17 years’ service, then successfully referred an unfair dismissal dispute to the CCMA (Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration), claiming constructive dismissal.

- Suffering health problems and involved in high-risk investigatory work which put his physical security at risk (hence no doubt his wearing a bullet-proof vest), he claimed to have been subjected to ongoing victimisation, bullying and harassment. His complaints included grievance disputes not being attended to, refusal of compassionate leave, poor work performance assessments, disciplinary and incapacity proceedings – the list goes on.

- Finding on the facts that there was “an accretion of conduct creating an increasingly oppressive work relationship for [the employee], with no functioning mechanism available to halt the deterioration”, the Court held that the employer had made the employment relationship intolerable. The employee was entitled to regard his resignation as a constructive dismissal and, that dismissal being an unfair one, the Court confirmed the CCMA’s compensation award of ten months’ remuneration.

|

|

Ponzi Schemes: Can Liquidators Claw Back 600% of Payouts?

|

|

“MTl's business clearly amounted to an unlawful ponzi-scheme, i.e. a fraudulent investing scam promising high rates of return to investors and generating returns for earlier investors with investments taken from later investors.” (Extract from the MTI judgment)

Recent media reports of the MTI (Mirror Trading International) liquidators making repayment demands of investors highlight once again the dangers of falling for “too good to be true” investment schemes.

The problem is that by their very nature, all pyramid schemes (including “ponzi” schemes) eventually fail, leaving the vast majority of investors with nothing but the hope of being awarded a partial dividend on their claims when the holding entity is eventually liquidated.

But what if an investor is one of the “lucky early birds” who got paid out before the scheme’s collapse?

Debunking the “early bird investor catches the worm” myth

A common myth is that the only losers in a collapsed pyramid scheme are those investors who didn’t get their money out in time, and that the “early birds” who did act quickly are winners in the equation.

The problem for them is that liquidators have wide powers to reclaim payouts made to investors (as creditors) before liquidation. The idea is that payouts by definition come from new money paid in by new investors, and that to be fair to them it is necessary to put everything back into the pot for all investors and other creditors to share according to their claims. But of course they only share in what’s left after all the liquidation costs and fees have been settled, and in a large and complex liquidation like MTI’s those costs will be particularly substantial.

The practical issue is that whatever was paid out to investors/creditors – both by way of the original investment and the “profit” on it – is likely to be claimed back by the liquidator. And the investor forced to repay everything is left with nothing but a concurrent claim in the liquidation.

Of course a liquidator’s prospects of recovery will be boosted if they can obtain a court declaration of unlawfulness of the scheme and invalidity of the investment contracts (as has already happened in the MTI liquidation), but let’s see how that could then play out in practice.

The liquidator’s options for recovery

To summarise the options available to a liquidator in recovering payouts made before liquidation -

- “Voidable preference”: If the payout was made within six months prior to liquidation and immediately thereafter the company’s liabilities exceeded its assets, it is repayable to the liquidator unless the investor can prove that that the disposition was made “in the ordinary course of business” and without intention to prefer one creditor above another. That could be hard to prove in the case of a pyramid scheme.

- “Undue preference”: If at any time a payout was made by the company with the intention of preferring one creditor above another, it is repayable to the liquidator if the company’s liabilities exceeded its assets at that stage. In this case, the onus is on the liquidator to prove the intention to prefer, but that may perhaps be easier to prove in a pyramid scheme scenario than in other corporate failure scenarios.

- “Disposition without value”: Monies paid out to a creditor at any time must be repaid to the liquidator if the company received no “value” in return, subject to –

- Where the payout was made more than two years prior to liquidation, the liquidator must prove that immediately thereafter the company’s liabilities exceeded its assets.

- But if the payout was made within those two years, the onus switches to the creditor to prove that immediately thereafter the company’s assets exceeded its liabilities. In the case of a pyramid scheme that may be impossible to prove.

Note that the creditor in such a case will also generally lose their claim against the company.

- “Collusive dealing”: If the liquidator can prove that a creditor colluded with the company to pay out monies with the effect of prejudicing creditors or of preferring one creditor above another, the colluder will not only forfeit their claim but can also be ordered to pay in a penalty of up to the same amount. A liquidator could for example try to prove that the investor/creditor was aware of the unlawfulness of the scheme at the time of the payout.

Even worse, could investors lose a lot more than they put in?

Media reports suggest that an MTI investor, who invested R20,000 and was paid out R21,000 shortly before liquidation, received a demand from the liquidators to repay not just his initial investment and profit, but for 600% of what he put in. The sum claimed (at date of writing) is R122,000, that being the current value of the bitcoin he initially invested – the argument being presumably that what was disposed of was “property” (bitcoin), in which case the liquidators would be entitled to reclaim either the bitcoin or its value at the date the disposition is set aside. The justification will no doubt be that that is what the company and its creditors as a whole have actually lost as a result of the disposition. If our courts agree with that view, being sued for a great deal more than the original investment will be a particular risk when the investment is a volatile asset like bitcoin.

The High Court has previously declared MTI an illegal and unlawful scheme and all agreements between it and investors unlawful and void, but that of course is only the first step for the liquidators in proving their claims against investors. Media reports suggest that many investors are lawyering up to oppose the claims so we must wait and see how it all plays out in the courts.

Regardless, the risk of not only losing the original investment but then also having to cough up a great deal more over and above that certainly does fire yet another warning shot across the bows of anyone tempted to invest in any scheme promising unrealistic returns. Prospective investors shouldn’t part with a cent until they confirm that the scheme is actually legitimate.

|

|

Budget 2024: Your Tax Tables and Tax Calculator

|

How much will you be paying in income tax, petrol and sin taxes? Use Fin 24’s four-step Budget Calculator here to find out.

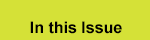

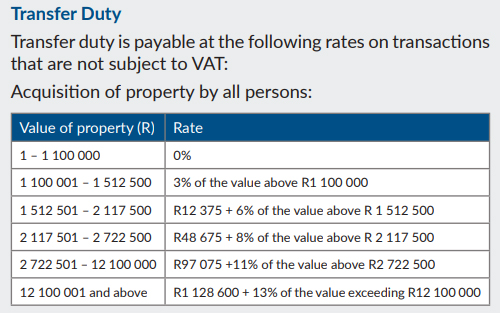

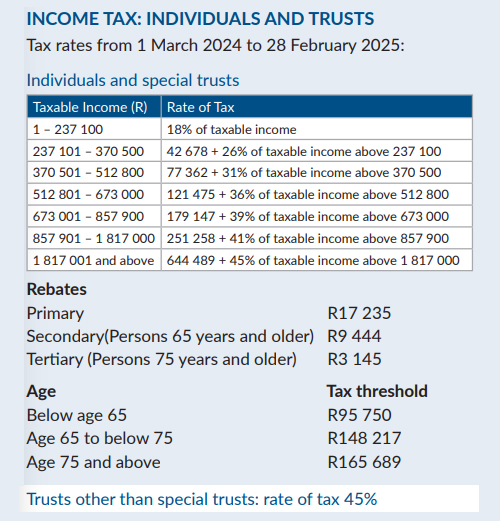

The unchanged transfer duty and tax tables, with a note on fiscal drag

Unchanged from last year, so taxpayers can breathe a sigh of relief that rates have not been increased as many forecasters had feared.

But the other side of the coin of course is that there is no inflation adjustment to the rates this year, which means that “fiscal drag” will leave you paying more tax if your inflation-linked increase pushes you into a higher tax bracket. Effectively, the buying power of your net income will fall. Plus if your property has increased in value into a higher threshold, your buyer will pay more transfer duty.

Source: SARS

Source: SARS

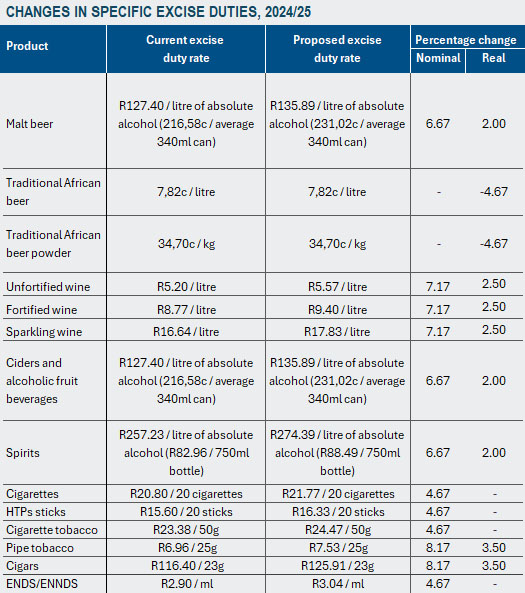

“Sin taxes” up – the details

Source: National Treasury

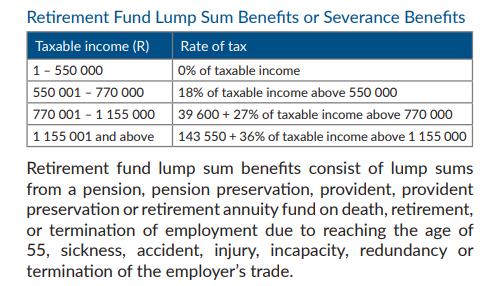

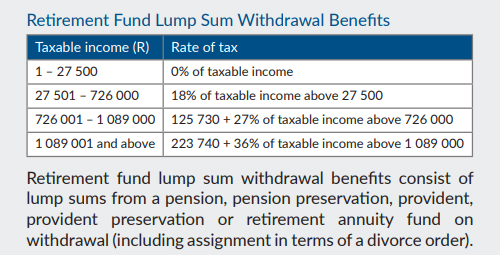

Retirement funding and the “two-pot” reform proposal

Source: SARS

Source: SARS

The proposed “two-pot” retirement reform: Per National Treasury: “Early access to retirement funds – “The two-pot retirement system will allow retirement fund members to make withdrawals from their retirement funds while they are still active members, so members need not resign to access part of their retirement benefits. ... This reform is proposed to come into effect on 1 September 2024. The National Treasury aims to finalise the legislative process rapidly in the next few months to ensure that industry and regulators can prepare for implementation. Policy research and engagement continues on the outstanding auto-enrolment, mandatory enrolment and consolidation retirement reforms.”

The proposals and their tax implications are complex and subject to change, but currently provide for a one-off withdrawal of up to R30,000 on implementation, and thereafter annual “savings withdrawal benefits”.

|

|

Effective 1 March 2024: New National Minimum Wage

|

|

The National Minimum Wage (NMW) for each “ordinary hour worked” has been increased from 1 March 2024 by 8.5% from R25-42 to R27-58.

Domestic Workers: Assuming a work month of 21 days x 8 hours per day, R27-58 per hour equates to R220-64 per day or R4,633-44 per month. The Living Wage calculator will help you check whether or not you are actually paying your domestic worker enough to cover a household’s “minimal need” (adjust the “Assumptions” in the calculator to ensure that the figures used are up to date).

|

|

Legal Speak Made Easy

|

|

“Prima facie”

Literally meaning “at first face” or “at first sight”, this term is often used in statutes and contracts to provide that a document is proof of the facts recorded in it in the absence of evidence to the contrary. A birth certificate or a bank certificate of balance are common examples. It can also apply for example to evidence given in a trial in the sense of being “proof (evidence) calling for an answer”. In other words, to be considered correct unless shown not to be.

|

|

Note: Copyright in this publication and its contents vests in DotNews - see copyright notice below.

|

| |

|

|

|

|